Why cash might be your riskiest investment

Plus: How big should your emergency fund be?

September 29, 2025

Cash is handy to have around. You can use it to pay for boring, essential stuff — like your mortgage and groceries — and for super-fun things, like a shiny new jetski. It’s also smart to keep some cash in a savings account to ensure you’re able to cover unexpected expenses, like car repairs. That way, you don’t have to take on wealth-annihilating credit-card debt to get by.

One hitch is that Canadians keep a lot of cash on hand — likely far too much, in many cases. A 2020 survey showed that about 41% of TFSAs and 22% of RRSPs were allocated to cash. More recent figures suggest that nearly half of TFSA owners hold only cash in their accounts. That’s not ideal for anyone trying to save for retirement or to reach other long-term saving goals; in fact, holding a mountain of cash can carry a lot of risk. Allow us to explain.

When cash makes sense

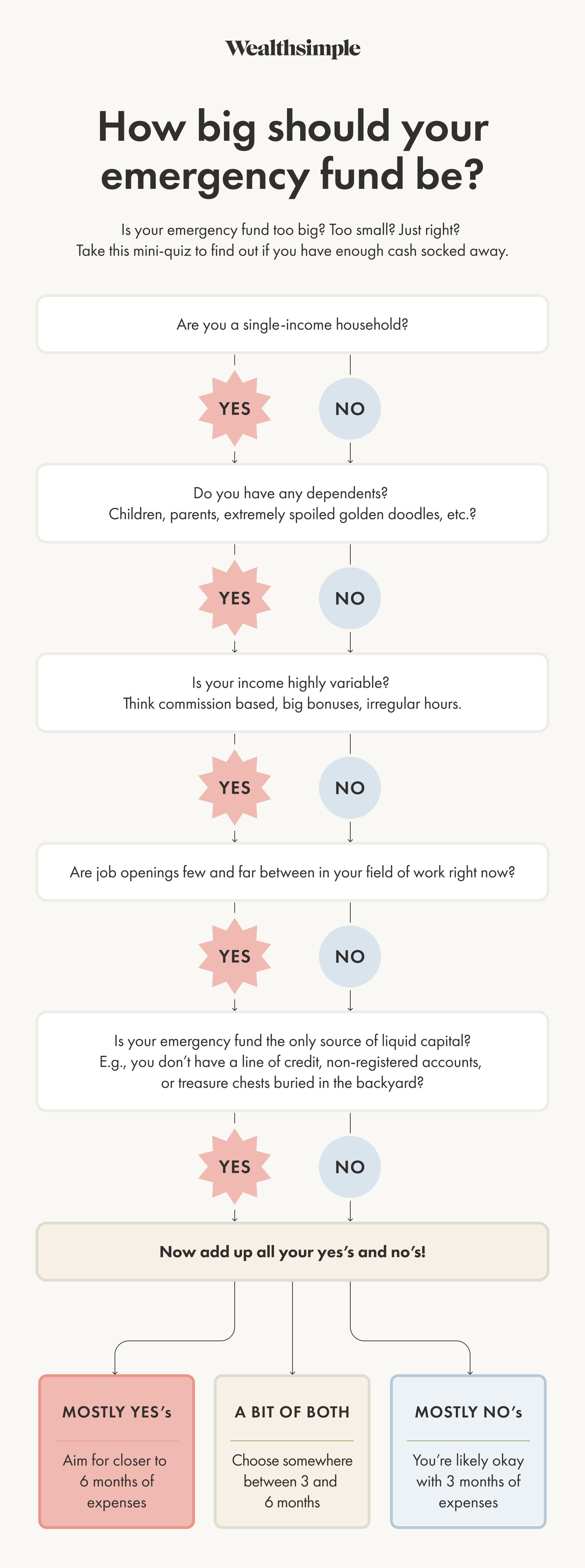

Before we get into the downsides, it’s worth saying that cash plays an important role in personal finance. Unlike stocks, which can swing daily, cash is steady in the short term. The balance of your savings account isn’t going to change unless you spend money, and you can access your cash anytime. That certainty is why advisors usually recommend keeping three to six months’ worth of living expenses in an emergency fund. Because when you need cash, you really need it, like in the event of a layoff.

It’s also wise to save in cash for near-term expenses, like a wedding or home reno, because you don’t want your money to plunge in value if the markets drop.

The hidden risks of cash under your mattress

Your considerations are different when it comes to saving for long-term goals. For retirement, in particular, your focus should be not on having lots of easy-to-access cash on hand but on having a sufficient income stream to support yourself when you stop working. And trying to create such an income stream with cash is a risky proposition.

That’s true in part because, while the perceived value of cash never falls, its real value does over time — thanks to inflation. As anyone who has lived through these past few inflationary years understands, cash in the bank gradually loses purchasing power as the cost of goods rises, diminishing your wealth.

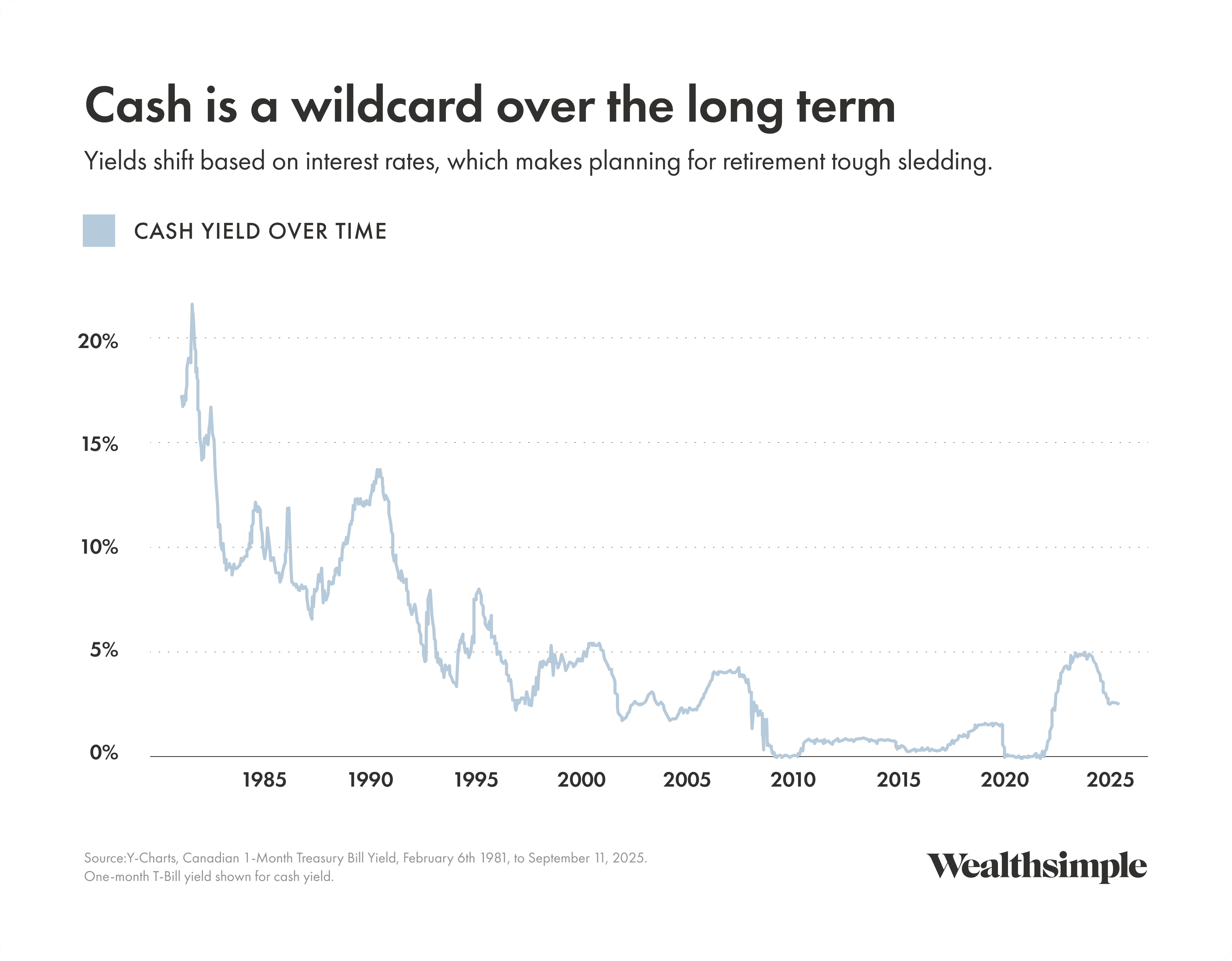

Another problem with cash is its uncertain rate of return. Cash yields change all the time based on interest rates. That’s potentially very bad for investors, because the difference between a 4% yield and a 1% yield, say, could mean the difference between having enough savings in retirement or not. But investors have no way of knowing what sort of yield they might get from cash over the long term. Maybe you’ll get close to 4%! But you could just as easily get 1%. And that unpredictability makes cash an unreliable long-term investment and income source.

You can see this uncertainty in the chart below, which shows a close proxy for cash yields since the late 1990s. Rates have swung wildly — from over 6% in the late ’90s, to nearly 0% after the 2008 financial crisis and again during COVID, and then back up to above 5% in 2023. The point is, cash offers no dependable long-term return. A saver in 2007 might have thought 4%–5% interest was normal, only to spend the next decade earning close to nothing (and miss out on a record run in stocks).

The surprising security of … stocks?

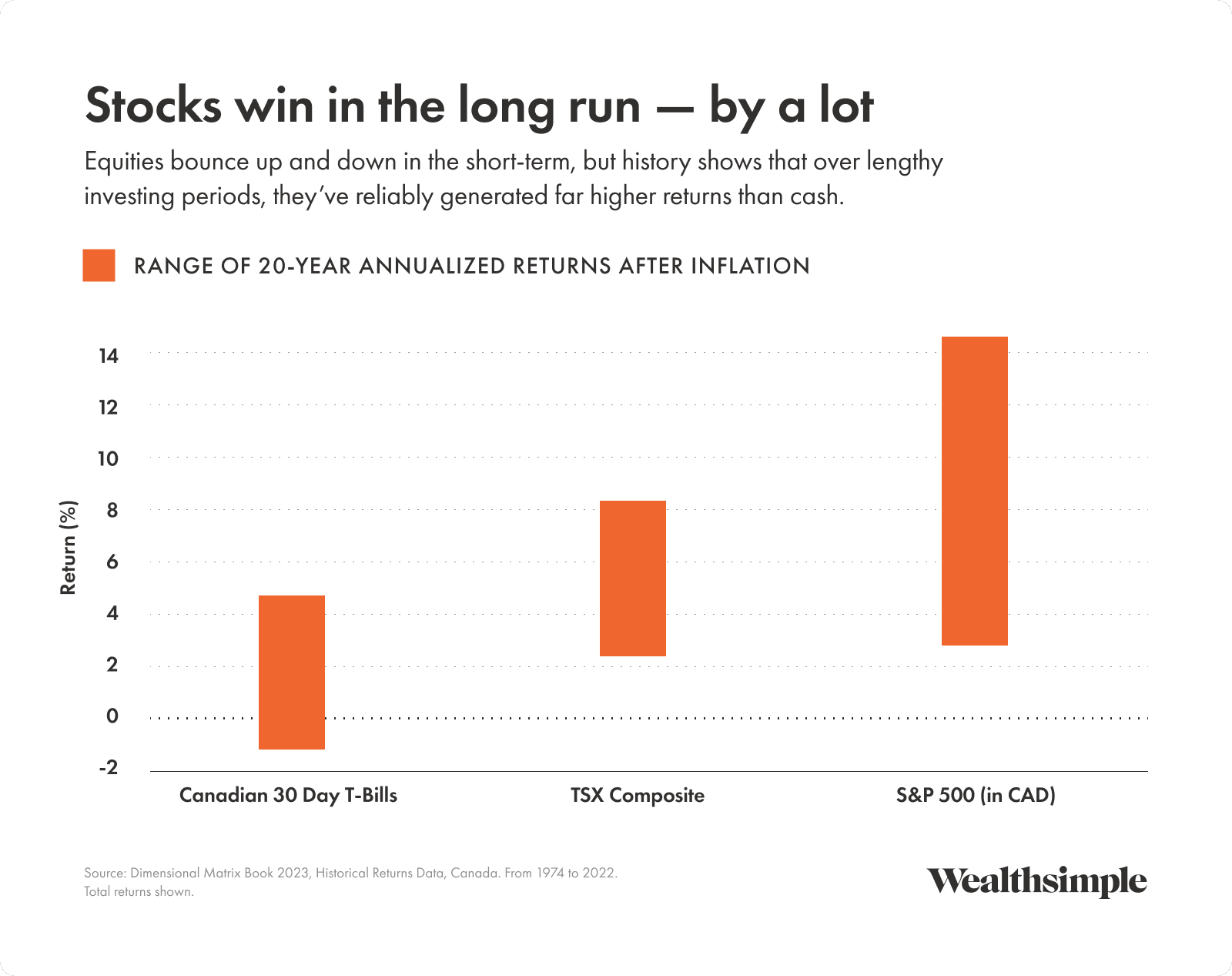

Stocks bounce around a lot, which is why the thought of having an equity-heavy portfolio makes some people anxious. But the thing is, over long investing periods, stocks have historically been one of the most reliable ways to build wealth and stay ahead of inflation. And they’ve certainly generated stronger, more dependable returns than cash.

Why? Because stocks are volatile in the short-term, and investors are rewarded for riding out the ups and downs with what’s known as a “risk premium” — or an extra return above cash. And, if you hold a big basket of diversified stocks (and bonds; more on those in a second), these high returns should compound and compound and generate reliable retirement income, even if a few individual stocks disappoint.

And here’s the counterintuitive part: if stocks fall in the short-term (which is painful, don’t get us wrong), you stand to make stronger future returns if you invest, because you’re essentially buying a company’s future profits at a discount. Cash doesn’t work that way — if yields fall, your future returns remain uncertain.

The returns speak for themselves: the below chart shows the range of after-inflation returns over the course of multiple 20-year horizons for cash and Canadian and U.S. equities, starting in 1974. We highlighted the best and worst outcomes, because investors should understand the full range of possibilities and plan for both the good and the bad. Cash’s best outcome was just 4.6% after inflation, while its worst was -0.6%, meaning some long-term cash savers lost wealth. By contrast, equities, despite bumps along the way, generated healthy positive returns, which for investors translates into higher expected future income streams.

Bonds, and their beautiful locked-in yields

Bonds are also important for long-term investors. Bonds can swing in price, but, unlike cash, they have set yields that allow you to lock in dependable income streams. For instance, the price of a 30-year government bond may bounce around, but its yield (5%, say) won’t change; no matter the price, you’ll still get regular coupon payments and your principal back at maturity.

That locked-in yield protects you from falling interest rates. With cash, your interest income resets whenever rates move — today’s 4% savings rate could be 1% next year. But if you own a 30-year bond with a 5% yield, you’ve guaranteed that income for decades. Put another way, bonds shield you from the risk of having to reinvest at lower future yields, while cash leaves you fully exposed.

The Upshot

Don’t get us wrong: cash is perfect for emergencies, everyday liquidity, and near-term expenses. But, as we hope we’ve made clear, it’s the wrong tool for reaching long-term goals. We know it’s somewhat ironic that assets that are risky day to day have historically provided the most long-term stability, but it’s true. If holding stocks or bonds makes you nervous, try to think of your portfolio not as a balance that should never fall, but as a machine built to produce reliable income over time. And the best way to build such a machine is not with cash.